Out Here on the Perimeter …

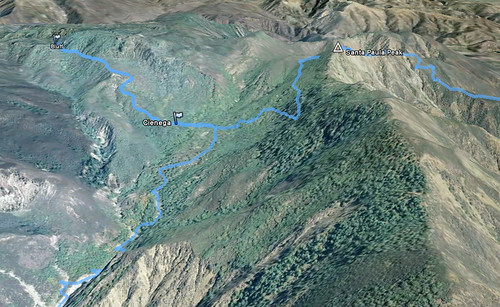

It was an unseasonably warm MLK Weekend that ZK and I grabbed two of the pack and headed up Santa Paula Canyon. We had three primary goals:

- Reconnoiter the damage done in the East Fork by the 2005 floods (the same ones that brought the hillside crashing down on La Conchita), and see what parts of the route had been lost (and which remained) from Big Cone to Cienega.

- Recon the route from Cienega to Bluff and the formations beyond, which has over the years become something of a “holy grail” site for our crew.

- Hit Santa Paula Peak on our way out of Santa Paula Canyon en route to Timber Canyon (this was the simplest of the goals).

Done, done, and done!

Day the First

After a brief skirmish between our pack and a few of the Recuerdo pack (no hard feelings, R pack, we know you were just protecting your turf … all thanks to the private landowners who let folks access this area), we headed past the last two Ferndale pumps and into the canyon. We saw two couples hiking during this early stretch. That was to be our last human contact for 51 hours.

The route up the main fork of Santa Paula Canyon sustained its own damage in 2005, and much of the stretch between the Echo Canyon confluence and where the old road bed heads onto the southern banks has been reduced to a wide, cobble-strewn flood plain. After crossing over to the service road and ascending that portion (all in very good shape, with the exception of the washout that’s rent a massive gouge in the route about half-way along the high portion of the road), we had a brief break at Big Cone and picked around the northern flanks of Hill 1989.

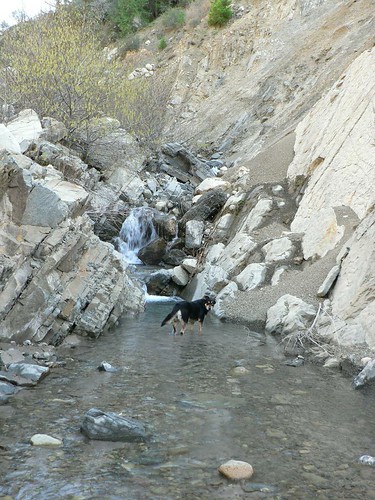

We dropped into the East Fork from Big Cone and almost immediately the trail fell off the edge of the canyon into the streambed. We followed some very deftly-placed blue flagging for a while, rock-hopping through alder-choked ravine and witnessing some slots where the debris flow that scoured those side channels must have been epic – canyon after canyon just obliterated by UPS truck-sized boulders on both sides. It was rather humbling.

Soon enough we came to a small guerrilla camp where somebody had built a good kitchen and left a very nice supply of fuel wood. There was a piece of the blue flagging we’d been following skewered into the center of the fire pit, and we therefore suspected this had been the turn-around point for the skilled trailblazer in whose wake we were traveling. (We subsequently christened this site “Blue Flag Camp”.)

Alas, this indeed proved to be the case. As helpful as the flagging had been, however, its loss didn’t deter our progress overly, as the going was slow – flagging or not. Every time we located a piece of the old route and followed it for a hundred yards or so, it would abruptly come to a sheer drop-off where the raging torrent that was the 2005 East Fork in storm had carved a new angle into the canyon. Back down we’d go, and again into the creekbed. I imagine we missed a few decent bits of trail once we decided to simply keep to the drainage, but I further imagine they’d have just led us to further hikers’ heartbreak anyhow, and so we continued our march/hop/slog eastward. (As an idle point of trivia, in the north- and east-ward arc we made, we saw only 11 minutes of sunlight the entire day, so well-shaded and so deep in the canyon were we.)

As we were reaching what the 1995 7.5’ quad indicated would be the narrowest portion of the canyon, we were forced to recalibrate our definition of the “hard” part. We were suddenly beset on all sides by imposing white-and purple-striped siltstone ravines, which — in ZK’s inimitable vernacular — were like “hiking through Plaster of Paris.” This from a man not given to hyperbole. In light of the recent rains, everything was very loose, very messy, and the dogs were up to their bellies in this ooze. And the ravine was steep. Our already-slow progress slowed further, so much that it didn’t feel like we were making any progress at all. The daylight was burning and we seemed to be barely moving.

We knew there was supposed to be a fairly level track somewhere to our left (north), but couldn’t find a sensible route up to it, and so just slogged on. Can muck be Class 3? This was.

Finally we scrambled over (or in my case, fell through and wriggled out of and over) a few debris jams near the top of this steep and time-sucking ravine, to emerge into a nice meadow hemmed in by big cone Douglas-fir. Another guerrilla camp stood sentinel here, and this one in turn we christened Camp Solitude.

With our remaining light waning, we knew we were close to where on the Santa Paula Peak quad the trail began its switchbacking climb up one of the southern drainages toward Cienega. We found a short piece of track along the river (had we backtracked, I suspect we may have found a piece of that elusive route that could have kept us out of the Grand Plaster of Paris Canyon). As had been the case with other pieces of trail, it petered out within a few hundred feet, so we opted for some dead reckoning. We agreed that if we didn’t find our way before we were critically low on light, we’d bivouac where we could and continue at first light the next morning.

We shot straight up the slope, tramping through duff 18 inches thick, eventually finding a game trail and following it on an easier grade. This game trail soon showed signs of a trail bed. Then I spotted evidence of decades-old trail maintenance just as ZK found some old fence posts buried in the hip of a huge, gnarled live oak. There was hope!

We continued along this old route for another mile, all the while closing in on where we were fairly certain the East Fork and Peak trails would converge. Quite some time after the sun dropped behind Santa Paula Ridge, we spotted an old 4×4 post with a metal USFS badge, and soon thereafter, came to a well-defined trail junction amidst heavy fern, conifer, maple, and oak cover. This stretch of the southern Los Padres has been spared the ravages of fire for most of the last century (I suspect the last fire here was the 1932 Matilija Fire) and easily competes with spots such as Santa Barbara’s Cold Spring Canyon for sheer lushness. It was akin to tramping in the Cascades or British Columbia.

We continued north, and just as my Garmin toggled over from day backlight to night backlight (indicating civil twilight), we walked into the glory that is Cienega.

ZK collected wood and got the fire going, I collected bottles and filtered water, and Lilly and Masha took a well-earned respite from point and perimeter duty, respectively. Fifteen minutes later the dogs were gnawing their ration and we were grilling lamb chops on the fire. A slow day, but a fine one.

We laid our bags out beside the fire and in the small window of sky afforded us by the trees forming the camp’s perimeter, we watched the nearly-full moon come into view. It wasn’t until later we actually zipped up the bags, so warm was the evening. Contrails from overhead jets sat static in the moonlight, so still was the air.

Day the Second

The next morning, we were in no hurry to do much of anything, and so scouted around the site, raking the area around the fire pit, clipping some wayward yerba santa and oak branches along the approach trail, and generally enjoying the environs of this very well-shaded site. In the late morning we packed our day bags, and headed out in search of Bluff camp.

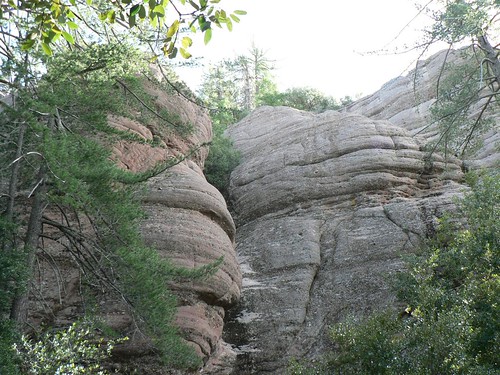

The ascent to Bluff is steep, there’s no reason to pretend otherwise. Given how little traffic it seems to receive, however, the trail was in remarkably good shape, and nowhere near as overgrown as we were expecting. I attribute some of this to the fact the route climbs through primarily “hard” chaparral (manzanita, chamise, mountain mahogany, etc.), which grows far slower than some of the other species. (The route was mercifully free of any thorned varieties of ceanothus.) The red sandstone formations that mark the southwest boundary of the Sespe Condor Sanctuary slowly drew closer, and in time we again found ourselves beneath magnificent groves of big cone Douglas-fir and sugar pine, specimens the would elsewhere find themselves amongst the Ents.

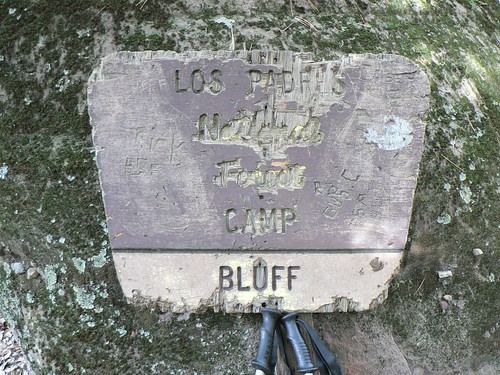

Sitting rather unassuming in all these towering conifers and massive sandstone monoliths and crevices, we found the skeletal remnants of a New Deal-era ice can stove and — half-buried beneath organic detritus — an old wooden sign proclaiming a small flat beside a spring-fed creek to be the vaunted Bluff camp. Were it not for two short logs ostensibly used as benches, I likely wouldn’t have made out the kitchen, to be honest … it had clearly been some time since anybody had used the camp. (ZK, as he is always wont to do, immediately endeavored to rebuild the fire ring, and it is now a very nice spot to cook indeed.)

We headed further up the thinning trail, investigating various crevices and dripping slots along the lower formations. Large flocks of ring-necked doves alighted from their roosts every time we rounded another corner. But for them and a few scrub jays, we saw little else. It was an eerily still spot.

We took our lunch in the old camp, and returned to Cienega for dinner.

Day the Third

The next morning, we didn’t loiter as we had the previous day, but neither did we rush our departure. We headed out toward the Peak/East Fork junction after breakfast, and climbed the long and lovely (and well-shaded) switchbacks toward the gap where the junction with the old route for San Cayetano Peak cuts east. Views were fantastic; we could see the snow-capped San Gabriels, the skyscrapers of downtown Los Angeles, seven of the eight Channel Islands, Lake Casitas, the peaks beyond the Matilija Wilderness, and the Topatopa Mountains. And this only from the saddle!

We watered the dogs and then continued to the junction with the Santa Paula Peak spur trail, dropping our packs and reaching the site of the old lookout just before noon. Cermak and Blakley both recount how the lookout was spared from the Matilija Fire by an ambitious backfire, only days after the Reyes Peak lookout was consumed. Only the footings and some odd cable and some brackets now remain; add another “to-do” to the list.

Here on Santa Paula Peak, obviously, the view was even better. In addition to those points we could spy from the saddle, now also in view was the tower upon which the Topatopa Peak lookout stood until consumed by the 2006 Day Fire.

From Santa Paula Peak, it was a steep, hot, rocky, tick-infested descent into Timber Canyon. I would certainly recommend against climbing it in such weather with dogs — as we saw a couple attempting to do just before we reached the ranch road — unless you’re carrying ample water for your quadruped companion(s).

After Santa Paula Peak, the rest of our journey did admittedly feel a bit anti-climactic. But knowing (to paraphrase Frost [twice]) exactly how lovely, dark and deep those woods beyond to be — and having learnt some of the East Fork’s secrets — we’re certain to again opt for the path less traveled next time ’round.

Leave a Reply